Musical Cryptology

Music and cryptology – two distinct fields with a surprising amount of overlap. At times this has resulted in the development of systems to hide meanings. Other times, the overlap has more to do with the cryptologists themselves. The allure of musical cryptology has engaged the interest of both cryptologists and musicians from many backgrounds, from composers to mathematicians and beyond. A quick internet search on terms like “musical cryptography” shows that this interest is alive and well today.

Music and cryptology – two distinct fields with a surprising amount of overlap. At times this has resulted in the development of systems to hide meanings. Other times, the overlap has more to do with the cryptologists themselves. The allure of musical cryptology has engaged the interest of both cryptologists and musicians from many backgrounds, from composers to mathematicians and beyond. A quick internet search on terms like “musical cryptography” shows that this interest is alive and well today.

Music – especially written music – is conveyed through symbols. Where there are symbols, there are possibilities for disguising messages by manipulating those symbols. In Western music, notes on a musical staff have letter names, and tones in a scale equate to syllables (think of the “Do Re Mi” song from The Sound of Music). But there are other types of musical symbols that can be cryptographically manipulated, such as spatial placement on a page of written music; duration of notes; or even how loudly a given note is played. Any aspect of music represented by symbols is a potential basis for a cryptographic  scheme.

scheme.

And what of the musicians and cryptologists themselves? Historically, there is a long-standing association between the skills of musicianship and cryptanalysis. Within American cryptologic circles, the best-known musician-turned-cryptanalyst was Lambros Callimahos. A professional flautist and serious student of cryptology, Callimahos enlisted in the United States Army in 1941. Within the National Security Agency (NSA), he was best known for his cryptologic and musical talents, serving as both a cryptologic instructor and a live musician for the workforce.

One of America’s earliest female cryptologists, Agnes Driscoll, was also a musician. Born in 1880 to a German immigrant family, she graduated from college in 1911. Over the next several years, she taught both music and mathematics. In 1918 – before women could vote in America – she enlisted in the United States Navy to serve her country in time of war. Soon her skills led her into cryptology, where in the 1920s she emerged as the U.S. Navy’s first professional cryptologist. She was instrumental in instructing

One of America’s earliest female cryptologists, Agnes Driscoll, was also a musician. Born in 1880 to a German immigrant family, she graduated from college in 1911. Over the next several years, she taught both music and mathematics. In 1918 – before women could vote in America – she enlisted in the United States Navy to serve her country in time of war. Soon her skills led her into cryptology, where in the 1920s she emerged as the U.S. Navy’s first professional cryptologist. She was instrumental in instructing  many of the junior officers who would go on to lead the Navy’s cryptologic cadres during World War II.

many of the junior officers who would go on to lead the Navy’s cryptologic cadres during World War II.

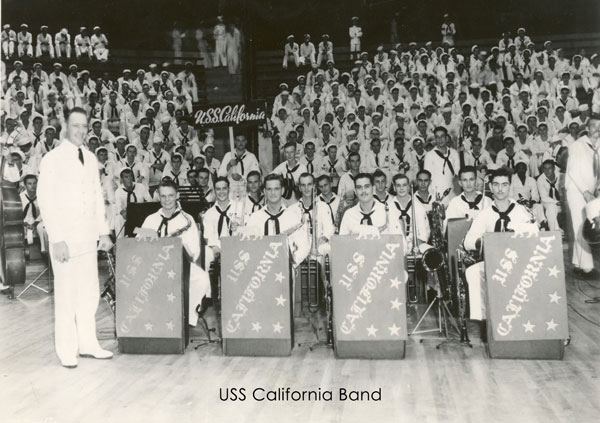

A number of other musicians, who found themselves unexpectedly working in cryptology, were among those in the United States Navy who survived the attack on Pearl Harbor. Serving in the bands of the USS California and several other ships, these men – some of whom barely escaped their sinking vessels during the attack – were called upon to serve in the cryptanalytic organization based at Pearl Harbor. Despite their lack of any previous cryptologic training, they made significant contributions to American wartime cryptology.

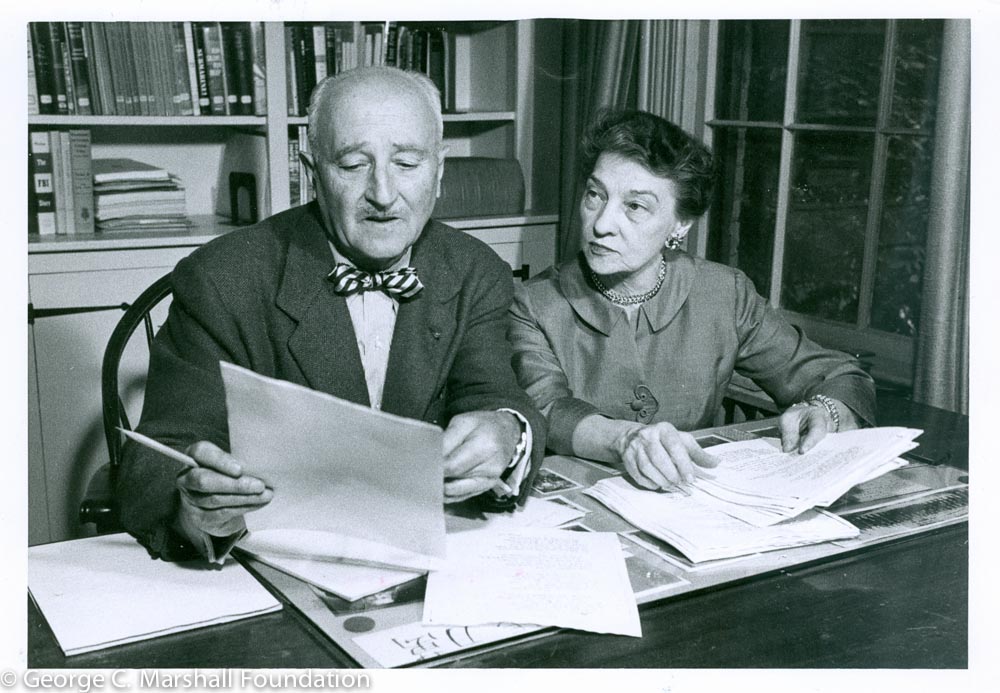

What did William Friedman, the defining force behind modern American cryptology, think of musical encryption systems? Sadly, not much. In 1944, a colleague passed along to Friedman a new musical cipher devised by a contact. After examining the system, the ever-polite Friedman replied that he was “sorry to say that I know of no authentic instance in which a cipher of this sort has been used in modern times for purposes other than books and movies.”

What did William Friedman, the defining force behind modern American cryptology, think of musical encryption systems? Sadly, not much. In 1944, a colleague passed along to Friedman a new musical cipher devised by a contact. After examining the system, the ever-polite Friedman replied that he was “sorry to say that I know of no authentic instance in which a cipher of this sort has been used in modern times for purposes other than books and movies.”

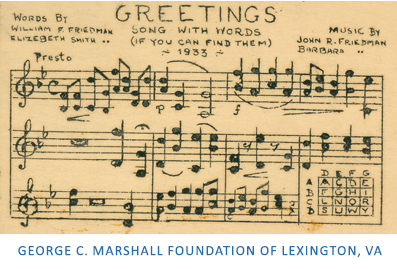

He did demonstrate his own interest in musical cryptology when devising a family holiday card with his wife Elizebeth. The card, pictured here, has some similarities to our current puzzle. Namely, the card states that it is a “song with words – if you can find them.” While our puzzle does not supply the reader with a grid of letters, it also has words. That is, if you can find them.

He did demonstrate his own interest in musical cryptology when devising a family holiday card with his wife Elizebeth. The card, pictured here, has some similarities to our current puzzle. Namely, the card states that it is a “song with words – if you can find them.” While our puzzle does not supply the reader with a grid of letters, it also has words. That is, if you can find them.

Whether you are a musician or not, and whether you share William Friedman’s estimate of musical ciphers or not, we invite you to participate in the tradition of musical cryptograms by solving the following example. (All words in lowercase and run together).